When a Tustin, Cal. man was indicted on immigration charges and accused of lying about his contact with a relative who worked for Osama bin Laden, the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR) blasted the case for its reliance on an informant it considered unreliable.

When a Tustin, Cal. man was indicted on immigration charges and accused of lying about his contact with a relative who worked for Osama bin Laden, the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR) blasted the case for its reliance on an informant it considered unreliable.

In interviews with Southern California Public Radio in February 2009, CAIR-Los Angeles Executive Director Hussam Ayloush said the FBI has been "hiring shady characters," and "a convicted felon, a con artist" who should not be believed.

Now, that same convicted felon is the foundation for a class-action lawsuit CAIR filed with the ACLU this week against the FBI. The Bureau, it alleges, sent informant Craig Monteilh into southern California mosques to conduct surveillance on people simply because they are Muslims.

The lawsuit represents three men active at the Islamic Center of Irvine and the Orange County Islamic Foundation, but seeks class action status on behalf of hundreds, perhaps thousands, of people who interacted with Monteilh. It also requests a court order requiring the government destroy all the information he gathered.

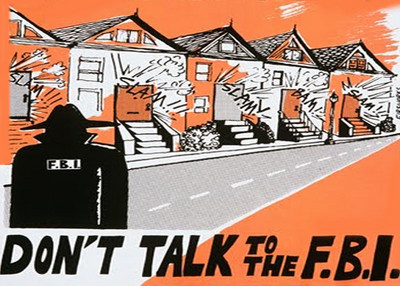

This action comes one month after CAIR officials claimed their organization had a "consistent policy of positive and constructive engagement with law enforcement officials." That defense was required after CAIR's San Francisco chapter posted a flier on its website, urging people to "Build a Wall of Resistance" by not talking with the FBI.

FBI officials have not commented on the lawsuit. The allegation that agents are sending informants into mosques without cause has been made for several years. FBI Director Robert Mueller has repeatedly denied this charge in public and under oath before congressional panels, saying "we do not focus on institutions. We focus on individuals. And I will say generally if there is evidence or information as to an individual or individuals undertaking illegal activities in religious institutions with appropriate high-level approval, we would undertake investigative activities, regardless of the religion."

Andrew Arena, special agent in charge of the Detroit FBI office, made it clear during a forum at the University of Michigan-Dearborn last year that informants are a tool used to target a variety of crimes. "We use [informants] in gang cases, we use them in public corruption cases, we use them in everything we do," he said. "We use them in counterterrorism cases ... Folks, we don't target religions. We don't target buildings. We can't do it. Under our rules, under the laws of this land, under the Constitution we can't do it. I would go to jail; agents would lose their jobs."

The lawsuit portrays the agents responsible for handling Monteilh as cavalier toward these concerns and legal safeguards. The agents "were well aware that many of the surveillance tools that they had given Monteilh were being used illegally," it says. Further, the plaintiffs claim:

"Agent [Kevin] Armstrong once told Monteilh that while warrants were needed to conduct most surveillance for criminal investigations, 'National security is different. Kevin is God.' Agent Armstrong also told Monteilh more than once that they did not always need warrants, and that even if they could not use the information in court because they did not have a warrant, it was still useful to have the information. He said that they could attribute the information to a confidential source if they needed to."

Unless Monteilh was recording his FBI handlers, it is his word against theirs. The lawsuit makes no reference to recordings that prove the allegations.

There are recordings that may show Monteilh's work did target people warranting scrutiny.

Though the case later was dropped, charges were brought against a man whose brother-in-law served as a bodyguard to Osama bin Laden and was designated by the United States as a terrorist. Ahmadullah Niazi was accused of failing to disclose that relationship and of lying about his travels to Pakistan.

During a February 2009 bond hearing, an FBI agent testified that Niazi referred to bin Laden as "an angel" and provided an informant – who turned out to be Monteilh – with taped sermons from an imam considered to have been a spiritual advisor for two September 11th hijackers.

Agent Thomas Ropel, III, who is not named as a defendant in the CAIR/ACLU lawsuit, testified that Niazi initiated conversations in which he "discussed conducting terrorist attacks and blowing up buildings."

The notions that mosques should not be breached during terrorism investigations can be debated. But a number of prosecutions show mosques have been used to further illegal activity. Among the examples:

In Detroit, a complaint charged Imam Luqman Abdullah with using his mosque to preach violent jihad and for weapons and martial arts training. Abdullah refused to surrender to FBI agents who came to arrest him, firing three shots before being killed by return fire. CAIR spent more than a year trying to blame the FBI for Abdullah's death, but separate reviews by the state of Michigan and the Justice Department's Civil Rights Division found the agents had acted appropriately.

In Tampa, three members of the Palestinian Islamic Jihad's governing board served as religious and administrative leaders of a mosque during the early 1990s. One, Ramadan Shallah, serves as the terrorist group's leader today.

The disappearance of young Somali men from Minneapolis believed to have joined the al-Shabaab terrorist group in Somalia was aided by meetings inside a local mosque.

Homeland Security records obtained by the Investigative Project on Terrorism under the Freedom of Information Act show that a prominent Virginia mosque was "associated with Islamic extremists" and "operating as a front for Hamas operatives in U.S." A report by Immigration and Customs Enforcement dated in December, 2007, said the mosque "has been linked to numerous individuals linked to terrorism financing" and "has also been associated with encouraging fraudulent marriages."

Any CAIR criticism of the FBI should be viewed in light of the Bureau's 2008 decision to cut off non-criminal communication with the group. That move is based on evidence the FBI discovered during a terror financing investigation which found that CAIR's founders were part of a Muslim Brotherhood-created Hamas-support network in America. CAIR itself is listed among the network's entities.

Last year, a Department of Justice official succinctly reported that no new evidence had emerged "that exonerates CAIR from the allegations that it provides financial support to designated terrorist organizations."

The outcome for the lawsuit against the FBI will take time. The record of the accusers, however, is already clear.