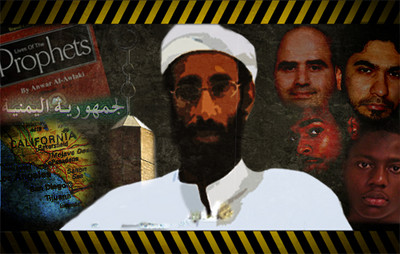

When Anwar al-Awlaki emerged as the clear inspiration behind a series of terror plots in 2009, his former associates in America insisted he was radicalized well after leaving the United States in 2002.

When Anwar al-Awlaki emerged as the clear inspiration behind a series of terror plots in 2009, his former associates in America insisted he was radicalized well after leaving the United States in 2002.

But in what might be his last published work, Awlaki explains that his involvement in violent jihad dated back to 1991, and that he hated the American government as far back as his college days.

"Spilling out the Beans: Al Awlaki Revealing His Side of the Story," appeared this week in the final edition of al-Qaida's English-language magazine Inspire.

The clarification flies in the face of claims by American Muslim leaders that he had been radicalized by Islamophobia after the 9/11 attacks, and motivated to violence following his 18 month imprisonment in Yemen, starting in 2006. At the heart of some Muslim leaders' argument was a desire to distance themselves from Awlaki's new public radicalism, and to twist the debate to focus on America's role in creating a vengeful monster.

"While employed at Dar Al-Hijrah, Imam Al-Awlaki was known for his interfaith outreach, civic engagement and tolerance in the Northern Virginia community," a statement from the imam's former mosque in northern Virginia said after Awlaki died in a U.S. drone strike last fall. "However, after Mr. Al-Awlaki's departure from the mosque in 2002 he was arrested by Yemeni authorities and allegedly tortured. It was then that Al-Awlaki began preaching violence," they claimed, while condemning America's assassination of Awlaki in a drone strike.

These claims were echoed by major outlets like the New York Times and National Public Radio. They portrayed Awlaki as a victim of his circumstances, and accepted the moderation of the "eloquent" preacher who claimed he could have been "a bridge between Americans and one billion Muslims worldwide."

But that image has not jibed with other accounts of Awlaki's life. Quotes from his early American speeches, accounts of his family life, and personal insights from friends show someone who idolized the Afghani jihad and Osama bin Laden's mentor Abdullah Azzam. Long before Awlaki preached America's destruction, he already believed that jihad was a key point of Islam and that America was against Muslims.

Spilling the Beans

In the Inspire article, Awlaki weaved the events of his life into a consistent narrative of hate.

"I have had experiences with the US government at quite a young age that most of you would not have in a lifetime. I have seen the other face of America," Awlaki wrote. From the beginning, Awlaki struggled with his relationship with America, while holding his own views close to heart.

Awlaki was born in the United States, but moved with his family to Yemen when he was 7. His father, a university professor in the capital Sana'a, became the country's agriculture minister. His father's clout helped him obtain college scholarships meant for foreign students even though he was an American citizen. Awlaki was influenced by his local environment to a much greater degree than previously believed. A New York Times biographical article states that the Afghani jihad against the Soviet Union was at the top of many people's minds in Yemen in the 1980s and early 90s, but not the Awlakis'. They were focused on using contacts to get a scholarship for their son.

But in his Inspire article, Awlaki wrote he already harbored pro-jihad sentiments and feared the United States saw him as a potential asset.

"Even though I was not fully practicing back then … I had an extreme dislike to the US government and was very wary of anything concerning intelligence services or secret orders," he wrote. "Thus, I was cold when it came to my relationship with the Office of International Students (which in my belief is a front for recruitment of international students for the government and is also a front from spying on them and reporting on them to the authorities). I also received an invitation to join the Rotary Club which I turned down."

The 1991 Gulf War in Kuwait triggered his hatred while a student back in the United States. "That is when I started taking my religion more seriously and I took the step of traveling to Afghanistan to fight," he wrote. "I spent a winter there and returned with the intention of finishing up in the US and leaving to Afghanistan for good. My plan was to travel back in summer, however, Kabul was opened by the mujahideen and I saw that the war was over and ended up staying in the US."

That account differs sharply from a 2010Time magazine profile. Awlaki wasn't interested in al-Qaida or Afghanistan after visiting in 1993, Time reports, and he "was depressed by poverty and hunger in the homes where he stayed."

Solidifying His Views

After returning to America, Awlaki claimed that he lost his scholarship in part due to his grades and because of what he called his fighting role and service as a Muslim Student Association president. Regardless, he now considered himself a fundamentalist and took up a new position reflecting this status when he moved from Denver to San Diego.

When Awlaki returned from Afghanistan he wore clothes popular with the mujahideen and often quoted Abdullah Azzam. He was also accused by a member of his Denver mosque of encouraging a Saudi youth to join jihad in Chechnya, shortly before he left for San Diego.

There, he became imam for the mosque Masjid al Ribat al Islami in 1996, chosen by "a group of students from Saudi [Arabia] and the Gulf states who formed their own mosque because they "were not happy with how things were run" at the moderate San Diego Islamic Center. Awlaki claimed that his conservatism and good fit with the community was important, because the government actively tried to infiltrate the mosque and recruit him to spy on his community, which he helped to prevent. He also claimed this was the reason why he was "falsely" arrested for soliciting prostitutes.

By 1998, Awlaki was fed up with the United States and ready to leave, but it took "three years and September 11" to "unwind" himself from the United States. During this time, Awlaki solidified his views of America and jihad.

Awlaki began preaching about the glories of jihad and the enemies of Islam in a lecture series from the late 1990s called "Lives of the Prophets." Evil surrounds Muslims in the West, he said, arguing that U.S. foreign and domestic policy are controlled by "the strong Jewish lobbyists." His disdain of Jews, whom he terms "the enemy from Day 1 to the Day of Judgment," is a common theme.

In one sermon, Awlaki prayed to Allah to "free" the al Aqsa mosque, the third holiest site of Islam, from what he terms "the Jewish terrorists" who he claims "have taken (it) over" and "give it back to the Ummah of Islam." He called for the broad institution of Sharia law as the basis for society. "Justice is in the heart of the judge," he said, "and that is why we can only have justice through a true Islamic system."

In another, Awlaki preached patience and persistence in pursuit of victory, saying people can get "fired up fast" by "a very hot" sermon about jihad and be "ready to go on the battlefield."

But those emotions can be lost "by the time you step your foot out of the masjid … Very easily fired up, and very easily we cool down," he lamented.

In the "Lives of the Prophets" lectures, well before 9/11 and before his time in a Yemeni prison, he called for a sustained commitment to jihad:

"Talking big is easy, but the sacrifice, and especially long-term sacrifice which jihad needs, that is difficult. Jihad is not only sacrifice, but it is a long term sacrifice. And that is where people fail. If you are asked to sacrifice in one time, you could be fired up by a speech, and then you would give out your money, for example, and you would sacrifice. That could happen. But when you're asked to sacrifice for a long period, then you're suffering hardship for a long time, that is what causes people to fail"

Sacrifice, he said, could take many forms and people should be willing to do whatever is required: "It could be your life, your time, your money, your family, it could even be the Islamic family or brothers that you are with, it could be the scholars that you love. Anything is possible."

Although his language became more direct in later sermons, calling for unlimited attacks on Americans, Awlaki proved that he already embraced violent jihad as a fundamental part of his worldview.