ISIS is steadily losing ground, leaders, and financial assets in Syria and Iraq. Growing numbers of frustrated jihadists are fleeing the "caliphate" or are unable to reach it.

ISIS is steadily losing ground, leaders, and financial assets in Syria and Iraq. Growing numbers of frustrated jihadists are fleeing the "caliphate" or are unable to reach it.

Western security officials have rightly raised the concern of an increase in ISIS attacks in the West due to losses in Syria and Iraq. But another likely result of this development is a tangible increase of jihadist violence against Arab-Muslim Middle Eastern and North African states, which ISIS seeks to topple.

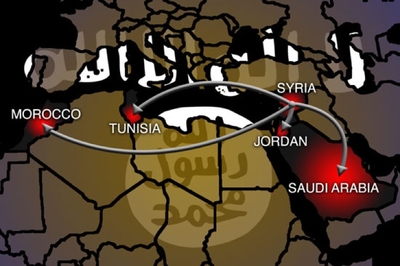

In fact, the threat to Arab-Muslim countries is significantly higher than the threat posed to Western Europe and North America, due to their proximity to ISIS's heartland, and the fact that the Middle East and North Africa easily form the biggest pool of ISIS volunteers - 11,000 in total, according to the International Study for the Centre of Radicalization.

Tunisian ISIS volunteers, estimated at 3,000, form the largest contingent of foreign fighters, followed by 2,500 Saudi Arabians, 1,500 Moroccans, and another 1,500 Jordanian jihadists.

The fanning out of jihadists from the crumbling caliphate in Syria and Iraq to neighboring Arab states represents an acute threat, particularly in light of ISIS's ideological dedication to toppling Arab governments it sees as apostates, Western-backed puppets, whose fate, they believe, should be the same as that of Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad and his fellow regime officials.

Failed states like Libya have already become alternative ISIS outlets, and the group's leadership can be expected to seek additional areas in the region to which to spread .

Violent Islamist volunteers who have gained combat experience in ISIS's battlefields could decide to target their own governments if they can return home. Alternatively, radicalized operatives in Arab lands who have never left their homes could decide to launch local attacks, and form their own terrorist networks under ISIS's virtual online influence.

Last week, Saudi Arabia announced the arrests of 17 terror suspects tied to three ISIS-linked cells who were planning to strike Saudi military targets, and other sites. ISIS also has been blamed for a string of terror attacks against Saudi Shi'ites during the past two years.

Like al-Qaida before it, ISIS views Gulf monarchies like Saudi Arabia as mortal enemies of its creed. It accuses the royal court of Saudi Arabia of usurping holy sites in Mecca and Medina, while forming alliances with the hated United States, and backing rebels in Syria that fought ISIS.

Turkey, for its part, is the first state bordering ISIS that recently launched a major ground offensive into Syria, in part to end ISIS rocket attacks on its border towns, and push the jihadist threat away from its border. The offensive, dubbed "Eurphrates Shield," is set to expand, and provided support for Sunni rebel groups that are at war with ISIS.

Despite being led by an Islamist government, Turkey is very much in ISIS's crosshairs. It endured a series of deadly ISIS attacks, including the June 28 suicide bombing atrocity against Ataturk Airport in Istanbul, and last month's ISIS suicide bomb attack on a Turkish wedding.

ISIS views Egypt's government as a secular abomination as does ISIS's local franchise, Wilyat Al-Sinai. It is active in northern Sinai, engaging in a bloody war against Egyptian security forces seeking to ultimately topple the Egyptian state. Those efforts included the downing of a Russian passenger jet over Sharm El-Sheikh last November. Such efforts by ISIS to harm Egypt's economy and national security could increase in the wake of ISIS's defeats in Iraq and Syria.

North African states, particularly Tunisia, which experienced its largest mass casualty jihadist act of violence in July 2015, when 38 tourists were gunned down on a beach, and Morocco, will be on high alert for the attempted return of their nationals who were ISIS fighters.

The Arab states that neighbor ISIS's caliphate – Lebanon and Jordan – face very concrete threats from ISIS elements flowing out of the caliphate.

Lebanon forms a prime ISIS target, due to the heavy involvement of the Lebanese Shi'ite Hizballah in Syria's civil war, and a desire by radical Sunni jihadists to punish the Iranian-backed organization for its support of the Assad regime.

ISIS remains committed to hitting Hizballah on its home turf of southern Beirut, as it already began doing last November, when it killed scores of people in two car bombs in Dahiyeh, Hizballah's stronghold.

The Lebanese Armed Forces (Lebanon's official military units) have also battled ISIS cells to prevent them from infiltrating over the Lebanese-Syrian border. This could destabilize a tense Lebanon, which is filled with sectarian tensions, and home to 1.5 million Syrian Sunni refugees.

ISIS targeted Christian villages in eastern Lebanon in June, and continuously threatens Lebanon's border with Syria.

To the east, Jordan has been a high profile participant of the U.S.-led coalition against ISIS, and its skilled security and intelligence forces have been working hard to prevent jihadists from spilling over from Syria, or sneaking in and hiding among the estimated 1.2 million Syrian civilian refugees in the Hashemite Kingdom.

In June, seven Jordanian security personnel were killed by an ISIS suicide car bomber on the Jordanian - Syrian border.

ISIS will not disappear from the failed states of Syria and Iraq, but it will likely change form. ISIS can maintain operating bases and continuing to strike as long as chaos, massacres, war – often sectarian in nature – and power vacuums characterize these lands.

The murderous brutality of Assad's Alawite regime and the sectarian bias of the Iranian-backed regime in Iraq will form an ongoing recruitment drive for Sunnis to join ISIS, even if that drive loses much of its prestige after the fall of the caliphate.

Western Europe and North America undoubtedly form high-value targets for a weakened ISIS, but Muslim countries surrounding ISIS are the first-line targets.

Yaakov Lappin is the Jerusalem Post's military and national security affairs correspondent, and author of The Virtual Caliphate (Potomac Books, 2011), which proposes that jihadis on the internet established a virtual Islamist state and sought to upload it in failed states. The book was published four years before ISIS declared a caliphate.