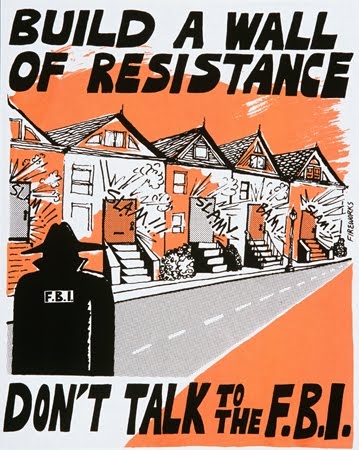

Several years ago the Investigative Project on Terrorism exposed the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR)'s deep-seated hostility toward law enforcement agencies. This hostility was vividly displayed in a poster produced by CAIR's California chapter that depicted a law enforcement officer, complete with dark trench coat and hat, lurking in a neighborhood as doors slammed in the officer's face. The poster exhorted followers to refuse to talk with the FBI and to "Build a Wall of Resistance."

Several years ago the Investigative Project on Terrorism exposed the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR)'s deep-seated hostility toward law enforcement agencies. This hostility was vividly displayed in a poster produced by CAIR's California chapter that depicted a law enforcement officer, complete with dark trench coat and hat, lurking in a neighborhood as doors slammed in the officer's face. The poster exhorted followers to refuse to talk with the FBI and to "Build a Wall of Resistance."

CAIR's anger grew out of the FBI's blacklisting the organization from outreach programs after an investigation into CAIR's involvement in financing Hamas, a State Department designated foreign terrorist organization.

CAIR spokesman Ibrahim Hooper claimed the poster was being misinterpreted and blamed that on "Muslim bashers," and an "Islamophobic hate machine." The local CAIR chapter eventually removed the poster from its website at the request of the national headquarters.

Outwardly, CAIR claims to want to work with law enforcement agencies to "protect our nation," but recent actions by its San Francisco chapter reveal that the policy to "Build a Wall of Resistance" continues to be its driving force.

Case in point, the Alameda County Sheriff's Department was awarded a grant from the Department of Homeland Security's Countering Violent Extremism program. The grant is to fund a program that would address the issue of inmate radicalization and also assist with the successful re-entry of released prisoners to the community.

In the initial application for the grant, the sheriff's department partnered with the Ta'leef Collective, a Muslim non-profit located in Freemont, Calif.

Sheriff's department staff met with Ta'leef founder Usama Canon, a former California Department of Corrections chaplain, and Micah Anderson, director of Ta'leef's wellness program, to formalize the grant application. Sheriff Gregory Ahern described Ta'leef as an organization that had "extensive experience in providing mental health and spiritual wellness services to justice-involved individuals."

One of the goals of the program was to "assist those individuals most susceptible to violent extremism." In other words, they wanted to help inmates avoid radicalizing influences from extremist groups seeking new members.

Acknowledging the threat of prison radicalization would seem to be a no-brainer given the studies that have been done on the issue both here and abroad. This was also the initial finding of the FBI's Correctional Intelligence Initiative program begun in 2003 which found the U.S. prison system "represents a sizable pool of individuals vulnerable to radicalization."

The most recent study by George Washington University's Program on Extremism found prison radicalization, "to be a major factor in how the threat of terrorism will unfold over the next decade."

In an earlier study, GWU found that prison radicalization was "evolving" and that "a broader approach is needed" which would include community and religious leaders.

Given the reality of the dual problem of radicalization & recidivism, who would object to a program that seeks a collaborative work between law enforcement and community organizations? Enter Zahra Billoo, executive director of the Council of American Islamic Relations, San Francisco Bay Area chapter. Billoo was on the job when her chapter published that "Wall of Resistance" image on social media.

She believes that the program unfairly targets Muslims and that law enforcement only uses the CVE programs to spy on the Muslim community. Billoo also believes that all DHS CVE funding is "tainted" because it comes from the Trump administration, even though the Obama administration started the program.

It would appear that CAIR is attempting to hide behind its political opposition to Trump even though the group was previously opposed to cooperating with law enforcement in general. Given statements like this from one of CAIR's outspoken leaders we should not be surprised for the renewed call for resistance against any law enforcement agency that seeks to develop a viable program that deals with violent extremism and prison radicalization.

Pressure from CAIR caused Ta'leef leader Usama Canon to withdraw from the program with the Alameda County Sheriff's Department. Sheriff Ahern replaced Ta'Leef with Oakland's Mind Body Awareness (MBA) Project. It should be noted that MBA director Micah Anderson still runs Ta'leef's wellness program.

This is not the only incident where CAIR sought to derail a partnership between law enforcement and community leaders in effectively dealing with radicalization.

In June, CAIR filed a lawsuit against the city of Los Angeles for accepting a CVE grant of $425,000 to combat radicalization.

Two months later, under pressure from CAIR and other Muslim activist groups, L.A. Mayor Eric Garcetti announced that he would not accept the DHS grant money.

CAIR may have taken a derogatory poster down from its website, but it continues to vilify any law enforcement agency that seeks DHS funding to combat radicalizing influences in its community.

CAIR's continued obstinacy only harms the Muslim community. It erodes the community's trust in law enforcement, a necessary component in combating crime and violent extremism.

The wall of resistance has become an impediment to combating violent extremism and radicalization. It needs to come down.

IPT Senior Fellow Patrick Dunleavy is the former Deputy Inspector General for New York State Department of Corrections and author of The Fertile Soil of Jihad. He currently teaches a class on terrorism for the United States Military Special Operations School.