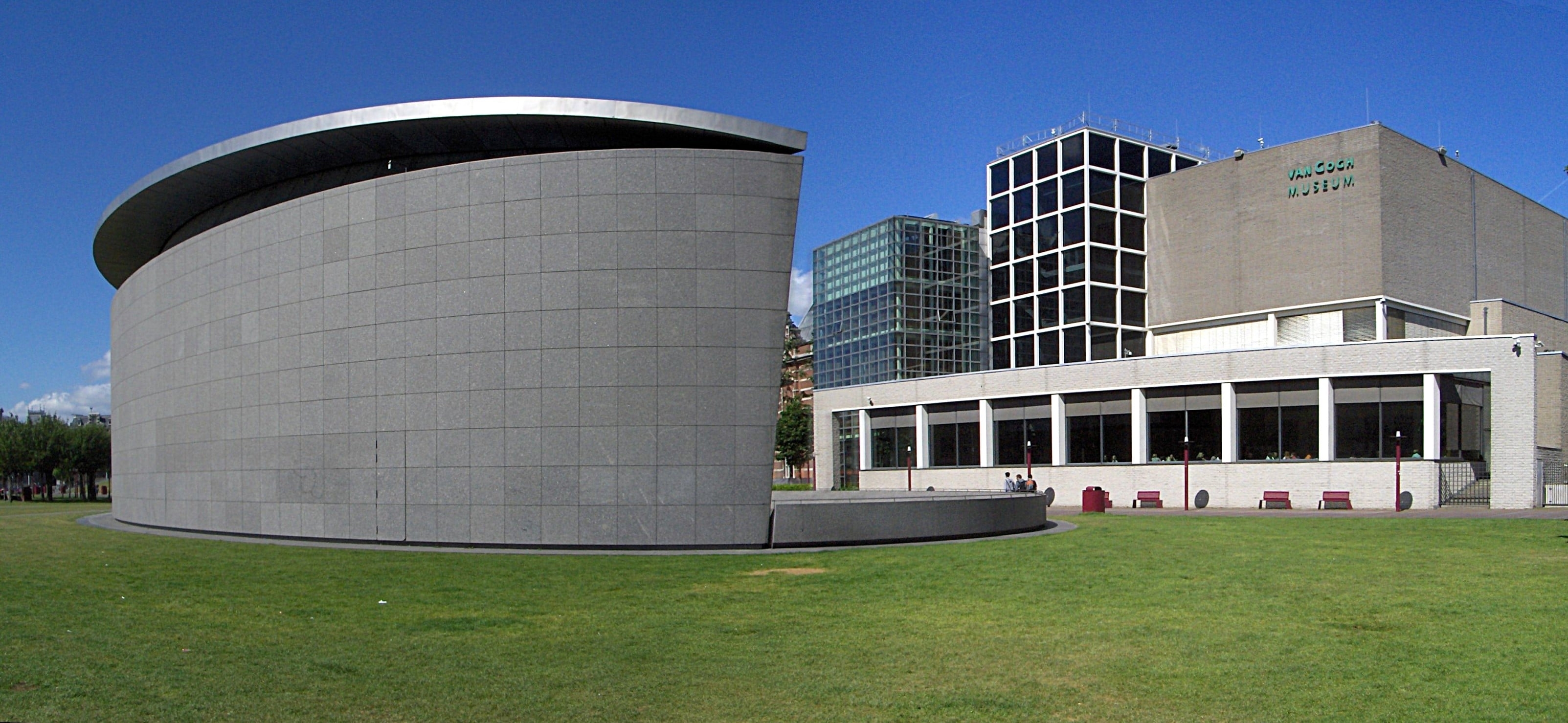

The Van Gogh Museum. |

Now, a museum dedicated to Van Gogh's oeuvre is asking whether it is "appropriate," in anno 2020, to exhibit a drawing by Degas.

To be sure, it's not just any drawing. The sketch in question depicts a bathing woman from behind, her derriere revealed in all its flesh and glory. It is also a drawing the Amsterdam-based Van Gogh Museum purchased last year at auction for the eye-widening price of $6 million.

Yet apparently even before acquiring the "Bather," part of a series Van Gogh is known to have especially admired, museum staff discussed the issue of whether it could or should be placed on view. Earlier this month, the Van Gogh Museum's new director, Emilie Gordenker, observed on Dutch national TV that while she is pleased the work is now hanging in the museum, she considers it important to address the question of "whether female nudes are appropriate for people of all cultures."

This, as everyone immediately understood, was code, a subtle way of asking, really, whether nudes should be exhibited at all in a museum located in a city where Muslims happen to live.

It's not the first time a question like this has been asked. In 2006, a Berlin opera house cancelled its performance of Mozart's "Idomeneo" out of concern for the "incalculable safety risk" posed by a scene depicting the severed heads of Mohammed, Jesus, Buddha, and Neptune. A year later, the Gemeentemuseum in The Hague bowed to pressure from Muslim radicals who threatened the museum if it exhibited photographs by Iranian art student Soorah Hera that depicted gay men disguised as Mohammed and his son-in-law Ali. The works were removed from the exhibition, and Hera was forced into hiding. And following the death threats and assassination attempts against several European cartoonists who had depicted the prophet Mohammed, a sin in Islam, gunmen stormed the editorial office of French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo in January 2015. Twelve people were killed and11 injured in the attack.

But since the Charlie Hebdo massacre, Western cultural leaders have tended to be less willing to compromise on these issues. More important, there is nothing blasphemous about the Degas drawing, nothing about it to send radicalized Muslims into a violent rage. It poses no "security risk" to the museum. What's more, no Muslim or Muslim group has threatened to take action, or even mentioned any discomfort with the drawing, at least publicly, nor has the museum indicated otherwise. And no one appears to have requested it not be placed on exhibition.

So why, then, the debate?

"The role of museums is changing," Gordenker told TV program "Buitenhof" on Feb. 9. "They are increasingly seen as part of the culture and society around them."

But is that really new? Many in the art world can recall the uproar when, in 1999, then-Mayor Rudy Giuliani threatened to cut off all subsidies to the Brooklyn Museum over its plans to include a painting by the artist Christopher Ofili of the Virgin Mary, created with oil paint, glitter, and elephant dung. (The work is now part of the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art.) The museum refused to bow to his pressure, and the public by and large stood with it. You do not censor art, the public declared. You especially do not censor art without first understanding it. And the censorship of public institutions is not an American value.

Even in the Netherlands, the public has long been involved in museum decisions. In the early 1990s, the Dutch government paid an American restorer $800,000 to repair a painting by Barnett Newman in the collection of the Amsterdam Stedelijk Museum after it had been slashed by a vandal. The restoration was a failure. The government sued the restorer, Daniel Goldreyer, but not before both the media and the public had expressed their outrage at the cost, and that it had been paid to a restorer outside the Netherlands.

But more importantly, who declared museums the center for such critical sociological debates, and when? Moreover, while America removes Confederate statues from its plazas and Holland's own national museum, citing the Dutch history of slavery, no longer uses the term "Golden Age" to describe 17th-century Dutch culture, shouldn't the real reason not to exhibit a $6 million Degas drawing – if it is to be censored at all – be the artist's rabid anti-Semitism?

Rather, we could talk about what there is to see in Degas' work: about his passion for depicting movement in a static image, about the line and color that so bewitched Van Gogh. Or we could talk about curator Fleur Roos Rosa de Carvalho's observation that "all the colors of the rainbow can be found in [the bather's] skin." We – or the museums – could teach people how to see.

In fact it was just this that, in 2005, inspired Holland's most celebrated curator, Rudi Fuchs, to bring a group of Moroccan-Dutch youth to the Rijksmuseum in an effort to teach them about art. The painting he selected: Rembrandt's "Jewish Bride" – a work, coincidentally, that Van Gogh himself once wrote brought him to tears. Not one student had a word to say about the fact that the bride was Jewish. Not one student had anything to say about the man's hand on the woman's breast. They talked about the painting while a reporter for Dutch national daily Volkskrant took notes. And when one student admired the gold jewelry the bride wore, Fuchs pushed her forward to the painting. "You don't see gold," he told her. "You see paint. Only paint." To another, he said, "Art is fantasy. You can see things in a painting that only you see. What do you see?"

But this is not the discussion Gordenker seems to have had in mind when she suggested that museums should stimulate conversation. Rather, it appears, she meant that a museum should create buzz so people will come – and this, she has certainly accomplished. The Degas drawing has now become the star attraction at a museum dedicated to the work of a different artist entirely, whose masterpiece sunflowers and sketches of peasants in the field will go unregarded as visitors seek out the fleshy buttocks of a comparatively unimportant "bather."

Yet meantime, museums as well as churches across the world still quietly spotlight their portraits of the Madonna nursing a naked baby Jesus. In the name of cultural sensitivity, should these now come down as well? Should the question even be debated? Rather than insisting on the normalcy of nudity, rather than teaching the importance of form and history and the painting of light along the curves of thighs and shoulders, rather than asking 'what do you see?,' opening the minds and eyes of those still stumbling in the dark, shall we just turn out the lights? Shall we stumble, too, in solidarity? Is that how it works?

Yes, it is important for a museum to inspire conversation. But not this conversation.

Because, as with the rampant "trigger warnings" on American campuses, such indulgences of small-mindedness and ignorance produce nothing, leaving only the slow death of the Enlightenment, of knowledge, the tragic, dark destruction of all we are, and all we could have been.

Abigail R. Esman is a freelance writer based in New York and the Netherlands. She is the author of Radical State: How Jihad Is Winning Over Democracy in the West (Praeger, 2010). Her next book, Rage: Narcissism, Patriarchy, and the Culture of Terrorism, will be published by Potomac Books in October, 2020. Follow her at @radicalstates.