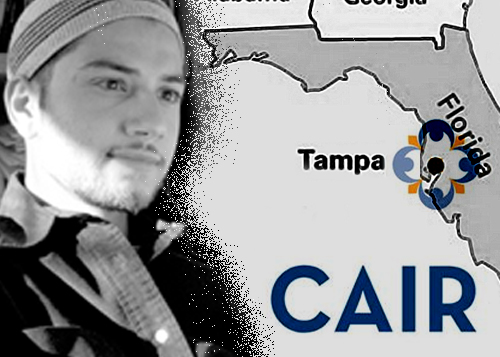

Hassan Shibly, who was one of the highest-profile officials at the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR), has been accused of spouse abuse and repeated harassment in a National Public Radio story published Thursday.

Hassan Shibly, who was one of the highest-profile officials at the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR), has been accused of spouse abuse and repeated harassment in a National Public Radio story published Thursday.

Shibly resigned as director of CAIR's Florida chapter in January, weeks after his wife went public with spouse abuse allegations. CAIR's announcement of his departure made no mention of those allegations, and thanked Shibly for leaving "the organization stronger than ever."

But his wife Imane Sadrati's appeal for money on the GoFundMe website helped spark a number of other allegations against Shibly. CAIR, in turn, was accused of covering for Shibly.

"I got married at a very young age," Sadrati wrote in the fundraising appeal, which has raised more than $32,000 as of Friday morning. "However, when I was 9 months pregnant with my first born; my marriage became volatile and abusive."

Shibly denies all abuse allegations. The couple is in divorce proceedings.

The Investigative Project on Terrorism obtained a 911 call Sadrati made on Dec. 25, three days before she posted the GoFundMe appeal. There was no imminent threat, she said, but "he attacked me in my home ... a couple of months back."

In the call, which can be heard below, Sadrati said she felt that he threatened to kill her "if I went and told anybody."

"I'm scared because I'm finally getting, like, out," she told the 911 dispatcher. "Like I'm finally taking action against him and I'm scared that he might come here and do something to me."

"He's been beating me for 12 years," Sadrati said, "and I'm done hiding."

In interviews with NPR, Shibly cast himself as the victim of her abuse. "She's using my position and the legal system to gain advantage in our ongoing legal divorce process," he told NPR. He also rejected independent allegations from former CAIR staffers and others that he sexually harassed and bullied people.

He responded to the NPR story with an Instagram post chiding people who use social media to "recklessly share utter lies and slander. As we abstain from food and drink during the days of this blessed month [Ramadan] let's not forget that such abstinence of what's normally permissible will bring us no benefit if we fail to abstain from what's always impermissible such us talebearing, gossip, slander and harming others."

Shibly admitted to NPR that he "did enter into religious marriage contracts with women outside his legal marriage." A failure to abstain, therefore, appears to be a big reason he's receiving this attention.

NPR deserves credit for publishing the story. Sadrati's GoFundMe video has been online more than four months. Social media has buzzed with allegations against Shibly, including on this open Facebook group. At its core, this is a story about a purported civil rights organization dogged by accusations of mistreating and discriminating against women, while its Florida chapter is run by a man accused of repeated harassment. But no Florida or other national news outlet seems to have pursued the story.

NPR still managed to accept and advance a false narrative about CAIR's origins:

In 1994, a handful of young Muslim activists in Washington, D.C., decided to push back against what they saw as the growing demonization of Islam in politics and pop culture.

The result of their organizing was CAIR.

This assertion that ignores a long, documented record tying CAIR's birth to the Muslim Brotherhood and a Hamas-support network operating in the United States during the early 1990s. Much of the information comes directly from the people who were there.

For starters, the FBI bugged a Philadelphia hotel meeting room in 1993, listening in as Muslim Brotherhood members and supporters spent a weekend discussing ways to "derail" the U.S.-brokered Oslo Accords. The peace deal included two elements vehemently opposed by the Brotherhood and its Palestinian offshoot Hamas: a recognition of Israel and the elevation of the secular Fatah movement over the Islamists in Hamas.

The recordings and translated transcripts of the Brotherhood's "Palestine Committee" meeting were admitted into evidence in the successful Hamas-financing prosecution against the Holy Land Foundation for Relief and Development and five former leaders.

The meeting was planned, convened and moderated by CAIR co-founder and longtime national chairman Omar Ahmad, described by the FBI as a "leader within the Palestine Committee." Nihad Awad, another CAIR co-founder and the only executive director it has ever had, also participated in the meeting, using the crude code name Samah – Hamas spelled backward – when referring to the terrorist group.

Other topics were covered. Among them, the FBI transcripts show, was a discussion about "establishing alternative organizations which can benefit from a new atmosphere, ones whose Islamic hue is not very conspicuous."

CAIR was formed the following summer "as a result of this" discussion, FBI Special Agent Lara Burns testified.

The evidence prompted the FBI to enact a policy in 2008 cutting off non-investigative contact with CAIR "until we can resolve whether there continues to be a connection between CAIR or its executives and HAMAS." The policy remains in effect.

While CAIR's true history remains largely ignored by news outlets, the NPR report paints a picture of an organization unwilling to confront chronic complaints against some of its leaders. It interviewed 18 people who worked at CAIR national and in prominent chapters.

Religious scholar Aslam Abdullah told the network that he has been told of numerous "credible allegations of harassment, sexual misconduct or unfair treatment" against powerful men in CAIR, but "women mistrust that CAIR will handle their claims seriously."

Hassan Shibly may have resigned. But unless the sources who spoke with NPR all are lying, CAIR's troubles extend well beyond one person.

Steven Emerson is Executive Director of the Investigative Project on Terrorism (www.investigativeproject.org), the author of eight books on national security and terrorism, the producer of two documentaries, and the author of hundreds of articles in national and international publications.

Copyright © 2021. Investigative Project on Terrorism. All rights reserved.